Abstract

Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention: Model Language, Commentary, and Resources is the recognized policy for effective district-level engagement for suicide prevention in schools around the country. Developed by thought leaders in education and suicide prevention, it is the policy Erika’s Lighthouse has supported and shared since its creation.

However, implementation and programming has been left up to individual districts, schools and educators. Erika’s Lighthouse depression education programming is uniquely qualified to assist in meeting not only suicide prevention recommendations but go beyond suicide prevention to embrace school mental health. Depression education is a more upstream, suitable alternative for many schools implementing programs because it seeks to educate, support and empower all students, including those struggling with mental health conditions and suicidal ideation.

Introduction

Education policy and schools have grappled with the topics of suicide prevention and mental illness for years, but only in the past few decades have educators recognized the importance of directly addressing these challenges.

There has been a continued debate over the role of schools beyond teaching only academics. However, schools should be working towards supporting the whole child. Just as school lunches fill a significant need in society – so does mental health education and intervention. Many students receiving mental health services are only receiving them in school. Supporting these students is vital for their academic and life-long achievement.

Identifying effective, evidence-informed, skills-based programs and solutions is key for administrators, nurses, social workers, counselors and educators in support of suicide prevention efforts. The search for practical, sensible education and intervention can seem overwhelming.

Choices range from increased mental health programming, direct suicide prevention curriculum, additional Tier 2 interventions or simply doing nothing for fear of creating problems as opposed to addressing them. Prior to selecting a path or a program, it is important to understand the problem.

Chapter 1: Understanding the Problem

Mental illness and suicide are closely connected. According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, “90% of young people who die of suicide have a mental health condition at the time of their death” (2). This demonstrates that suicide prevention programming should not be offered independently of broader mental health education.

Suicide

Specifically relating to suicide, the statistics are disturbing and widespread (1):

- Suicide is the 2nd leading cause of death for young people 10-24, making up 19.2% of all deaths among young people in 2017.

- In the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, more than 1 in 6 high school students in the U.S. reported having seriously considered attempting suicide in the 12 months preceding the survey.

- More than 7% of students (about 1 in 13) reported having attempted suicide in the preceding 12 months.

- Rates are rising among young people, “rates of suicidal thoughts, plans and attempts all increased significantly, and in some cases more than doubled, between 2008 and 2017“.

Depression & Other Mental Illnesses

The co-occurrence of suicide and mental illness is well-documented. 90% of those who die by suicide have a mental health condition, yet 54% of those youth were undiagnosed at the time of their death (2). This underlines the need for more education and awareness.

We also know that depression is widespread among teens:

- In a Pew Research study, 96% of teens listed depression and anxiety as problems among their peers with 70% identifying them as serious problems (3).

- Depression is the most common mental health disorder.

- Each year, 1 in 8 teens experience depression (4).

- Depression has increased dramatically over the past decade. “Between 2009 and 2017, rates of depression among kids ages 14 to 17 increased by more than 60%. The increases were nearly as steep among those ages 12 to 13 (47%) and 18 to 21 (46%), and rates roughly doubled among those ages 20 to 21. In 2017—the latest year for which federal data are available—more than one in eight Americans ages 12 to 25 experienced a major depressive episode” (1).

- In 2017, 31% of high school students reported symptoms of depression, a significantly higher number than the number who have been diagnosed (5).

- Depression is the most common mental health disorder that is accompanied by co-occurring disorders. 3 out of 4 teens with depression have also been diagnosed with anxiety and half have been diagnosed with behavior problems (6).

- Almost all the youth that experience depression in adolescence will experience it again as an adult (7).

- 50% of mental health disorders begin before the age of 14 and 75% occur before 24 (8).

Treatment and Barriers to Care

We know that intervention and treatment for youth experiencing mental health challenges are vital and successful.

We know that intervention and treatment for youth experiencing mental health challenges are vital and successful.

Treatment works:

- 71% of teens with depression get better through treatment.

- 81% of teens with anxiety get better through treatment (8).

Accessing services can be incredibly challenging, demonstrated by the fact that nearly two-thirds of teens receiving mental health services access them only in school (9). This underlines the urgent need for robust school policies, including depression education, for school staff, students and parents.

In 2016, only 41% of the 3.1 million adolescents who experienced a major depressive episode within the past year received treatment (10). Around 60% of all teens with a mental health disorder do not receive the treatment they need (9).

The reasons for these youth going untreated are many:

- Parents may be likely to overlook depression and other internalizing disorders because they often manifest in less disruptive ways than externalizing disorders such as ADHD.

- Parents lack knowledge of the symptoms of depression and other mental health disorders.

- Teens are sensitive to issues of confidentiality and often are reluctant to ask health providers even general health questions due to confidentiality concerns.

- Teens often view varying degrees of “storm and stress” as normative during adolescence and not cause for seeking medical attention.

- Depressed adolescents often underestimate the severity of their symptoms.

- Lack of health insurance or restrictions by insurers on coverage for particular services (19).

- Shortages of providers with specific expertise in adolescent mental health (19).

- Stigma is a significant barrier to treatment and is predictive of adverse mental health outcomes:

- Teens have a pressing desire to be normal.

- The public inaccurately views individuals with depression as potentially violent.

- Depressed adolescents, especially girls, are more likely to be viewed as less popular and less likeable by their peers than their non-depressed counterparts (7).

Chapter 2: Go Upstream: Depression Education is Suicide Prevention

We know that depression is far more prevalent than suicide. There is a unique and incontrovertible link between depression, mental health and suicide. These two statements support the idea that effective depression education IS suicide prevention.

We know that depression is far more prevalent than suicide. There is a unique and incontrovertible link between depression, mental health and suicide. These two statements support the idea that effective depression education IS suicide prevention.

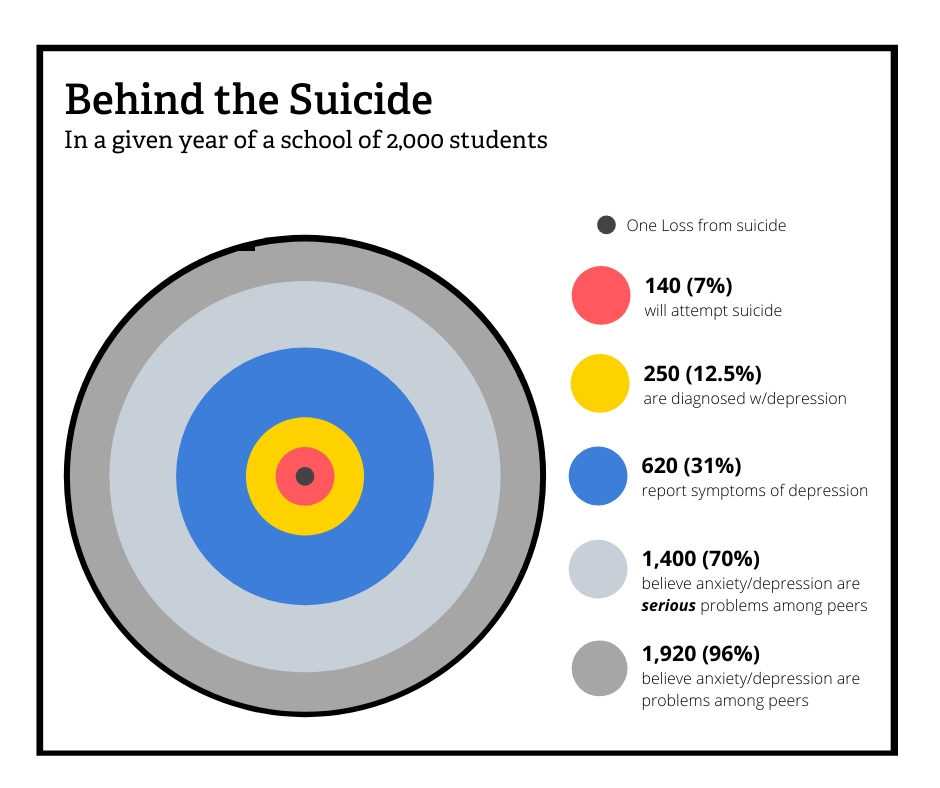

In a given year, out of a school of 2000 students:

- 1,400 (70%) of students will identify depression and anxiety as serious problems among their peers, reinforcing the importance of education and understanding these disorders (3).

- 620 (31%) of teens will report symptoms of depression (5).

- 250 (12.5%) of teens will experience depression (4).

- 140 (7%) of teens will attempt suicide (2).

- 1 student may lose their life to suicide.

We know schools benefit from a broader discussion of mental health, such as depression because it:

- Is relevant to the entire population of students.

- Addresses many of the issues that impact a students’ ability to learn and perform any given day – attendance, achievement, behaviors, and others.

- Reduces stigma and builds a climate of good mental health within a school.

- Promotes early identification, intervention and help-seeking among teens.

- Supports all students, not just those with suicidal ideations.

- Allows impactful, meaningful conversations among all students to help them understand their peers.

Similar Warning Signs & Symptoms

Depression education informs and supports suicide prevention efforts. The decision between which path to take is not an either/or – but a both/and solution. The warning signs and symptoms of depression and suicide are remarkably similar – likely because the leading mental health condition related to suicide is depression.

The chart below demonstrates the similarity in signs and symptoms between depression and suicide. Because of this similarity, it is highly likely that depression education will help students struggling with suicidal ideation and promote help-seeking behaviors.

The comparison exemplifies how depression education may benefit the early identification and intervention of youth at risk of suicide. Considering that 31% of high school students reported having the symptoms of depression in a given year, early identification of those students is imperative. Teaching about depression allows all students the opportunity to learn about the signs and symptoms, offers them the opportunity to request help and teaches them important help-seeking skills. It not only helps students struggling with mental health challenges self-identify, but also those experiencing suicidal ideation.

| Warning Signs and Symptoms | Depression (11) | Suicide (12-14) |

| Feelings of sadness, tearfulness, emptiness or hopelessness | • | • |

| Angry outbursts, irritability or frustration, even over small matters | • | • |

| Loss of interest or pleasure in most or all normal activities, hobbies or sports | • | • |

| Sleep disturbances, including insomnia or sleeping too much | • | • |

| Tiredness and lack of energy, so even small tasks take extra effort | • | |

| Reduced appetite and weight loss or increased cravings for food and weight gain | • | • |

| Anxiety, agitation or restlessness | • | |

| Slowed thinking, speaking or body movements | • | |

| Feelings of worthlessness or guilt, fixating on past failures or self-blame | • | |

| Trouble thinking, concentrating, making decisions and remembering things | • | • |

| Unexplained physical problems, such as back pain or headaches | • | • |

| Poor performance or poor attendance at school | • | • |

| Using recreational drugs or alcohol | • | • |

| Self-harm and unnecessary risk taking | • | • |

| Avoidance of social interaction | • | • |

| Frequent or recurrent thoughts of death, suicide, or suicide attempts | • | • |

| Giving away belongings or getting affairs in order for no reason | • | |

| Saying goodbye to people as if they will not be seen again | • | |

| Talking about suicide or death, even in a joking way | • |

Chapter 3: Important Components of Curriculum

Examining the inclusion of a suicide prevention or mental health program is an important step. “The literature on evaluating SMH (School Mental Health) programs suggests that such programs can be effective. Evaluations examining 8 short-term changes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes resulting from SMH programs have consistently shown that such programs can improve staff, faculty, and student knowledge of mental illness; skills for identifying and referring students with symptoms; and attitudes toward mental illness” (16).

Identifying an effective suicide prevention program can be challenging. There are several areas of consideration for schools – and only school districts and educators know what is best for their students.

Response to Intervention/Multi-Tiered System of Support

Response to Intervention (RtI) and Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) are commonly accepted models for academic and behavioral intervention. Effective RtI/MTSS not only requires an understanding of the three tiers along with acceptable methods for achieving them, but also high-quality Tier 1 interventions to help identify students who may require additional assistance at school. “Tier 1 or primary prevention programs are designed to increase awareness of and sensitivity to mental health issues in students—for example, by supporting students coping with stress and encouraging student help-seeking behaviors” (16).

Building mental health inclusive school cultures and reducing stigma takes the education and involvement of all youth and educators in a school. A foundation of shared staff beliefs and vocabulary is critical. The idea is that “staff across the school/district understand & accept their role in the positive teaching and managing of student behaviors” (15). This can be accomplished through professional development and building an inclusive culture.

An effective Tier 1 intervention program provides educators and students the opportunity to learn, understand and empathize with others regarding mental health issues and challenges. It also builds a foundation for future instruction and intervention. The program should generate a common vocabulary in a school community, ensuring administrators, educators, students and parents are speaking the same language.

Tier 1 curriculum and programs also inform Tier 2 and 3 interventions, both through shared vocabulary, ancillary supports, resources and professional development. “Tier 2 or secondary prevention programs target subgroups of students identified as at-risk for mental health disorders but not yet exhibiting symptoms. These programs are often designed to provide staff or faculty skills to identify and respond to specific mental health issues or populations (e.g., suicide prevention, substance use)” (16).

Tone & Style

The tone and style of any adopted program is key to its success. Allowing students to absorb and process the information is integral to students understanding and accepting. Programs should be positive, hopeful, authentic and informative. Using real students talking about real problems from diverse viewpoints allows every student to engage with the content. Programs that are dark, sensational, or unrelatable will be unable to break through today’s noise and may be less impactful. They may even cause more harm than good, scaring students from seeking assistance.

In addition, representation matters. Identifying programs that allow students of all backgrounds to feel seen, heard and validated is important. Mental health has racial, ethnic, socio-economic and cultural significance that makes finding diverse programs a key to success. Supporting every student and their diversity promotes equity.

Evidence-Informed

It is important that programming is evidence-informed, skills-based and built on existing best practices. Believing a program is effective and having data that demonstrates it are very different. Well intentioned efforts are not always the best effort. It is imperative for schools to ensure programs have and will accomplish the established objectives.

Trauma-Informed

Students come to the classroom with many different values, cultural and religious beliefs, and ideas about these topics. Teachers should keep in mind that because their students come from many backgrounds and traditions, some may have difficulty sharing ideas and discussing these issues with their peers.

When a student has experienced trauma of some sort in their life, it may have an impact on their ability to thrive and be healthy. Infusing language and guidelines to support students that have experienced Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) is important when having sensitive and personal discussions in classrooms.

Delivery

Considering where, how and why programs are delivered is a vital part of successful implementation. Particularly in the area of suicide prevention and mental health education, ineffective or poorly implemented programs may be damaging. Programs must be accessible, turn-key, and have the support of educators and mental health professionals.

In a Tier 1 setting, finding the correct home for a program may be challenging. It is important for students to learn in an environment that is inclusive, open and appropriate; led by informed, supportive educators and professionals. An ideal setting for suicide prevention and mental health education is within a health education curriculum. Most, if not all, students are required to complete some degree of health education and the link between physical health and mental health is well established (17).

A health education setting is a place to ensure every student receives the curriculum and uses the same vocabulary and foundation. This model promotes equity and meets the standards set by the Model School Policy.

Skills-Based Education

If a health education classroom is the ideal location, then ensuring the program meets National Health Education Standards, including utilizing skills-based learning, is key to continued promotion of help-seeking behavior. “Today’s state-of-the-art health education curricula reflect the growing body of research that emphasizes:

- Teaching functional health information (essential knowledge).

- Shaping personal values and beliefs that support healthy behaviors.

- Shaping group norms that value a healthy lifestyle.

- Developing the essential health skills necessary to adopt, practice, and maintain health-enhancing behaviors” (18).

Skills-based education is designed to not only educate students with knowledge but also empower them with the tools and skills to act upon that information through role-playing, practice and modeling behaviors. It can be especially helpful in mental health education. Traditional delivery of information to students about suicide and mental health may be beneficial within a specific classroom, but the experiences, challenges and mental well-being of students can change rapidly during adolescence. Non-skills-based programming may not set students up for success later and be insufficient for the potential future onset of mental illness.

Skills-based education is designed to teach students how to access valid and reliable information and services throughout their lives. The ability of a student to self-identify and seek help later should be key to a district’s suicide prevention and mental health supports.

Chapter 4: Meeting Prevention Policy Recommendations

The Model School District Policy on Suicide Prevention: Model Language, Commentary, and Resources was designed to “outline model policies and best practices for school districts to follow to protect the health and safety of all students.”

“The purpose of this policy is to protect the health and well-being of all students by having procedures in place to prevent, assess the risk of, intervene in, and respond to suicide. The district:

- Recognizes that physical and mental health are integral components of student outcomes, both educationally and beyond graduation.

- Further recognizes that suicide is a leading cause of death among young people.

- Has an ethical responsibility to take a proactive approach in preventing deaths by suicide.

- Acknowledges the school’s role in providing an environment that is sensitive to individual and societal factors that place youth at greater risk for suicide and helps to foster positive youth development and resilience.

- Acknowledges that comprehensive suicide prevention policies include prevention, intervention, and postvention components.”

Prevention is a significant piece of this recommendation and what is addressed in this white paper. The Model School Policy includes five focus areas within Prevention:

District Policy Implementation

The Model School Policy recommends naming suicide prevention coordinators at both the district level as well as within specific school buildings. These individuals could be administrators, counselors or mental health professionals that work together to ensure a seamless delivery of prevention efforts. The policy recommends a best practice of a suicide prevention task force to oversee all efforts made up of diverse stakeholders. In addition, all staff are encouraged to report students they believe may be at risk.

Erika’s Lighthouse supports these efforts and suggests expanding the scope to educate students about depression and mental health and to work closely with existing school mental health initiatives and coordinators. The close link between suicide and mental illness and the effective implementation of depression education inextricably links these issues.

Staff Professional Development

The Model School Policy supports professional development for all school personnel about the warning signs of suicide, “ ideally at least one hour every year for all school staff, including bus drivers, cafeteria staff, coaches, security, etc. — on suicide prevention, including education about mental health and warning signs or risk.”

Erika’s Lighthouse strongly agrees with this recommendation and can provide the necessary training to schools. An important aspect of this professional development should include how to respond if a child approaches an adult for help. In addition, a coordinated approach through a single provider can further the adoption of a shared vocabulary across the entire school community, an important aspect of a high-quality Tier 1 program.

Youth Suicide Prevention Programming

The Model School Policy recommends “developmentally appropriate, student-centered education materials shall be integrated into the curriculum of all K-12 health classes and other classes as appropriate.” In addition, “the content shall also include help-seeking strategies for oneself or others and how to engage school resources and refer friends for help” and “schools shall provide supplemental small-group suicide prevention programming for students. It is not recommended to deliver any programming related to suicide prevention to a large group in an auditorium setting.”

Erika’s Lighthouse supports these recommendations. The middle and high school programs developed by Erika’s Lighthouse meet this criteria and are specifically designed for health education classrooms with further encouragement to be co-taught by a mental health professional within the school. In addition, all Erika’s Lighthouse programs should be completed in small-group, classroom settings to engage students in meaningful conversations and to track student emotional health.

Curriculum is not the only aspect of Erika’s Lighthouse offerings. A number of additional supports are offered such as self-referral cards and informational bookmarks that also promote help-seeking behavior, positive mental health behaviors and link to the Erika’s Lighthouse Parent Handbook on Childhood and Teen Depression. The importance of these ancillary materials to support school-based activities and policies is essential to a seamless implementation of suicide prevention and mental health education.

Publication and Distribution

The Model School Policy states, “This policy shall be distributed annually and be included in all student and teacher handbooks, and on the school website. All school personnel are expected to know and be accountable for following all policies and procedures regarding suicide prevention.”

Parental Involvement

The Model School Policy indicates that, “Parents and guardians play a key role in youth suicide prevention, and it is important for the school district to involve them in suicide prevention efforts…

Parents and guardians who learn the warning signs and risk factors for suicide are better equipped to connect their children with professional help when necessary.”

Erika’s Lighthouse strongly agrees and has a desire to change school cultures to create more affirming and inclusive communities surrounding mental health discussions and stigma reduction. Erika’s Lighthouse provides three forms of support for schools looking to engage parents:

- The Parent Handbook on Childhood and Teen Depression is designed to educate and support parents with children struggling with depression and mental health challenges. It was written by parents, for parents, and provides practical information regarding depression, treatment and promoting positive mental health. It is available in English and Spanish.

Schools may choose to send home a Parent Letter (English or Spanish) to inform parents about the Erika’s Lighthouse curriculum. - Through a collaborative partnership called Shine Light on Depression, Erika’s Lighthouse has partnered with Anthem, Inc, National Parent Teacher Association, American School Health Association and JetBlue Airways to create the Family-School Community Conversation Workshops, designed to promote meaningful dialogue between schools and parents about mental health.

Chapter 5: Teen Engagement and Empowerment

While classroom programs, parent involvement and professional development are essential to suicide prevention and mental health education, even more can be done to build inclusive school cultures where discussing, sharing and experiencing symptoms of mental illness or suicidal ideation are approached with dignity and students are comfortable seeking and receiving help.

A highly effective tool to accomplish this is through peer-led programming. Teens can build their own inclusive cultures around mental health discussions through Erika’s Lighthouse Teen Empowerment Clubs. These clubs offer teens opportunities to raise awareness, break stigma and spread empathy through our Awareness into Action Activities.

Implementing a Teen Empowerment Club

Implementing a club in a school depends on school policy, teen interest and sponsor/advisor availability. They can be driven by school personnel or by teens themselves and the Erika’s Lighthouse team is available to support their efforts. A number of resources have been developed to assist sponsors/advisors, including the Start a Club Guidebook and a follow-up piece on how to Mobilize Your Club available on the Erika’s Lighthouse Resource Portal.

Teen Empowerment Clubs are supported through direct grant funds for activities, an online store for branded materials sold at cost, t-shirts for members, and direct support from Erika’s Lighthouse staff.

Awareness into Action Activities

These turn-key initiatives allow teens to empower one another and encourage challenging conversations that young people want to have. The activities are composed of Mindful Moments, Positivity Promoters, Education Efforts and You Are Not Alone Reminders designed to meet the needs of individual school communities and offer a diversity of approaches. Many of the activities available were created by Teen Empowerment Clubs around the country and shared with the broader community.

Follow the Footprints

An example of an Awareness into Action Activity is called “Follow the Footprints”. Students place printed and cut-out footprints around the school that lead directly to a Social Worker or Counselor’s office – promoting help-seeking behavior and reminding teens that support exists. The footprints have facts about mental health and depression to educate youth. Some schools have implemented this activity on St. Patrick’s Day with a “pot of gold” in the social worker’s office for teens to find. This activity was created by teens in an Illinois-based club and is a great example of how teen-led initiatives can bolster existing school policies.

Chapter 6: Prevention Implementation Checklist

Erika’s Lighthouse is available to support every district, school or educator planning to implement effective suicide prevention and mental health education within their district or school. The checklist below is intended to guide and direct how to utilize Erika’s Lighthouse curriculum and resources for effective implementation.

Review & Prepare

- Assign a suicide prevention/mental health education coordinator for the district.

- Assign a suicide prevention/mental health education coordinator for each school.

- Consider creating a suicide prevention/mental health task force to engage multiple stakeholders.

- Review materials by creating an always-free Erika’s Lighthouse Resource Portal account.

- Develop a plan for implementation within district/school including involved parties, roles and responsibilities, processes, flow of communication and next steps.

Train

- Coordinator(s) should contact Erika’s Lighthouse staff to discuss best practices, allotted time and format of program implementation.

- Front Line staff, including health educators and other mental health professionals should be trained on best practices and how the program will be implemented within the district/school.

- Encourage educators or mental health professionals to seek additional guidance from Erika’s Lighthouse, if needed.

- All school personnel should receive education that covers suicide prevention, depression education, shared vocabulary and how to respond if they are the trusted adult and/or worried about a student.

Educate Parents

- Send all parents a letter (English or Spanish) informing them the school is utilizing Erika’s Lighthouse curriculum and providing them a common vocabulary.

- Provide parents a copy of the Parent Handbook Bookmark, available in English and Spanish, so they can access additional information about adolescent depression.

- Host a Parent Night Workshop, in collaboration with a PTA or PTO, to create meaningful conversations among parents about teen mental health. Developed through Shine Light on Depression.

Educate Students

- Implement Erika’s Lighthouse curriculum for middle or high school students.

- Distribute Teen Bookmarks (English or Spanish) for teens to remind them how to access support and promote positive mental health.

- Ask students to complete self-referral cards so they can be promptly contacted by a mental health professional.

Engage Students

- Identify 2-3 students to lead a Teen Empowerment Club in the school.

- Read Start a Club Guidebook.

- Speak with Erika’s Lighthouse staff on best practices and support.

- Read Mobilize Your Club.

- Host a Kickoff Meeting and plan the first Awareness into Action Activity.

Follow-Up

- Engage stakeholders to evaluate success of efforts.

For assistance at any point, please contact Erika’s Lighthouse at info@erikaslighthouse.org.

Conclusion

Depression education is an upstream, suitable alternative for many schools implementing programs to educate, support and empower all students, including those struggling with mental health conditions and suicidal ideation.

Curriculum from Erika’s Lighthouse should be seriously considered for meeting a district’s needs for mental health education and suicide prevention. All programming and support through Erika’s Lighthouse is available at no cost.

Engage with Erika’s Lighthouse today by:

- Creating an always-free Resource Portal account.

- Contacting us at info@erikaslighthouse.org.

- Exploring our programs and resources.

Your school can be a more inclusive, supportive and encouraging environment with Erika’s Lighthouse.

AUTHORS & EDITORS

Author:

Brandon M. Combs, MNA, Executive Director, Erika’s Lighthouse

Lead Editors:

Kristina Kins, MSW, Director of Program Development & Operations, Erika’s Lighthouse

Peggy Kubert, LCSW, Sr. Director of Education, Erika’s Lighthouse

Ilana Sherman, MPH, Director of Education, Erika’s Lighthouse

Elaine TInberg, Vice Chair of Board, Erika’s Lighthouse

External Editors:

Jessica Lawrence, Director, Cairn Guidance

Sally Stevens, LCSW, PPSC, M.Ed., Los Angeles Unified School District

Nancy Watson, LCSW/CADC, Lake Forest Country Day School

Guest Editors:

Lisa Honcharuk, Manager of Marketing & Engagement, Erika’s Lighthouse

Meade Means, Development & Operations Assistant, Erika’s Lighthouse

SOURCES

- https://time.com/5550803/depression-suicide-rates-youth/

- https://www.datocms-assets.com/12810/1586436500-k-12-schools-issue-brief-1-14-20.pdf

- https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2019/02/20/most-u-s-teens-see-anxiety-and-depression-as-a-major-problem-among-their-peers/

- https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/adolescent-development/mental-health/adolescent-mental-health-basics/index.html

- https://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/facts-and-stats/national-and-state-data-sheets/adolescent-mental-health-fact-sheets/united-states/index.html

- https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3551284/

- http://neatoday.org/2018/09/13/mental-health-in-schools/

- https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/mental-health/school-psychology-and-mental-health/school-based-mental-health-services

- https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.htm

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/symptoms-causes/syc-20356007

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/suicide/symptoms-causes/syc-20378048

- https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=teen-suicide-90-P02584

- https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Teen-Suicide-010.aspx

- https://www.interventioncentral.org/sites/default/files/workshop_files/allfiles/ES_BOCES_Session_1_RTI_Beh_16_Jan_2019_PPT.pdf

- https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2012/RAND_TR1319.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953617306639

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/characteristics/index.htm

- https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Child_Trends-2013_01_01_AHH_MHAccessl.pdf